A Small Place

"The Caribbean Sea is no longer ours...It can't be observed as being so big and so beautiful anymore. It's now so much money."

What’s Inside

The Book: Publication history

Impressions: Caribbean writing about autonomy and disaster, 19th century propaganda art, troubled freedoms

The Writer: How writing A Small Place changed Kincaid, in her own words

Paraphernalia: Two film reccommendations and a podcast trio of readings, critiques and Antiguan history telling in the Tenement Yaad

At the Close: An upcoming IG live with a Caribbean publisher, the monthly Zoom link up and Discord details.

The Book

Jamaica Kincaid wrote A Small Place as an essay originally meant for The New Yorker when William Shawn (1907-1992) was editor. He loved what he had seen of it. Before it could be published there was a staff change, preceded by a sale.

In 1985 Peter F. Fleischmann (1922-1993), co-founder of The New Yorker along with his father, sold a controlling stake of the magazine to Advance Publications, a part of the Newhouse family’s publishing empire. (Perhaps like me you are familiar with the Newhouse name because you have long wondered when they will end Anna Wintour’s reign at US Vogue, please gods.) Despite all the goss that surrounded news of the sale, S. I. Newhouse Jr (1927-2017) promised “not to tamper with The New Yorker's special identity”, then “forced out” William Shawn a little over a year later.

Newhouse appointed Robert A. Gottleib (1931-) in his place. He found Kincaid’s essay to be “very angry. Not badly written. Angry.” That might have been the end if Shawn had not encouraged Kincaid to make it a book. He was in the perfection position to do so with his new job as a consulting editor at Farrar, Straus & Giroux, the publisher of her previous books. Released in June 1988, the first chapter was published under the title “The Ugly Tourist” in the Harper’s Magazine September 1988 issue.

Impressions

The return home is always through air to alight by the sea. The opening lines to Kincaid’s essay and third published title address the tourist but I found it easy to bypass them and find myself within the flight trajectory home. There are innumerable Caribbean writings with a character looking through the window, stepping off the plane in return.

Right before a plane lands at Cyril E King airport on St. Thomas, there is a span of seconds when you can stare out the window and see only ocean below. For those seconds, it looks as though you landed right in the water. And then, right as murmurs in the cabin give way to held breath, the runway appears at almost the last possible moment, and the plane lands.

This is always my favourite part of coming home: the way the water comes up to meet you and then you've arrived. If you get the right crowd, the first timers will actually applaud, and there’s this sense of pride as if you'd performed a trick for them yourself, even though you had nothing to do with it. It's like saying, “I almost had you, didn't I? Welcome to my home.”

That’s an excerpt from Virgin Islands author Cadwell Turnbull’s sophomore release No Gods, No Monsters (Blackstone Publishing, 2021) The thoughts are not the character’s present but collected past memories. On that flight he is asleep “like the dead” and doesn’t open his eyes until a flight attendant wakes him up to an empty cabin.

What happens when we die? Do we forget? Do we reincarnate into something else? Were we human to begin with? When we die… do they forget?

Heat swirls into my skin as soon as I step off the plane. I walk in with tourists. Tourists in floppy straw hats and Red Sox baseball caps, tourists in shorts embellished with tiny anchors, tourists with pre-packaged tans they’d sprayed or rubbed onto their frosty skin the night before. Tourists already moaning about the eighty-degree heat once they deboard the plane. They have prepared for everything except the sensation of heat stomping onto their skin.

Those are the opening lines to Sara Bastian’s short fiction “When We Die” (2020) published in Pree Lit’s Ecocide issue.

Turnbull’s and Bastian’s writing connect to A Small Place from different timelines. Both of Turnbull’s novels are speculative fiction that address, among many things, matters of autonomy and self-governance. What might happen if islands with a colonial history (and present) had to reckon with an alien invasion? How would a local politican approach political representation if she could transform into a different kind of creature who ran with hurricanes? In her story, Bastian speculates on a future inflected by past in which even submerged islands with evolved inhabitants cannot escape capitalistic valuation as disaster tourism destinations.

Perhaps Kincaid would say that Antigua had been a disaster tourism destination for a long time. This is my second time reading her potent critique on “the impact of European colonization and tourism” (from the blurb). It broke the long drought after I read and suppressed my memory of Annie John in high school many years before in the late 90s. Under the influence of her Calabash Literary Festival appearance in 2014 I bought it (probably because, of all her books available there, it was the cheapest) and got her signature.

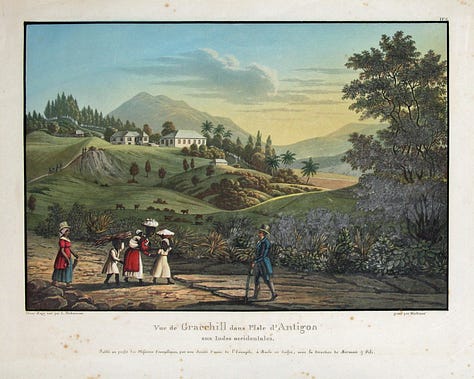

With this second read I noticed what had not seemed important before. In the FSG edition each of the four sections is separated by a page with a detail from an artwork. I recognized it because the first one is on the cover of an earlier hardcover FSG edition. All four details in the book are from three different early 19th century aquatints attributed to either L. Stobwasser or Johann Stobwasser depending on the source.

According to this description the Moravian church mission in Antigua commissioned the pieces to promote their work on the island. The first detail in A Small Place is from the first aquatint Vue de Gracehill dans I’Isle d’Antigoa aux Indes occidentales. “This view depicts the Moravian estate called Grace Hill, located near the island’s capital of St. John; it is now part of the village of Liberta.” In the detail is what appears to be a mixed woman in “European dress” behind a Black woman with children carrying provisions.

The third detail in the book is from the second aquatint Vue de Gracebay dans l'Isle d'Antigon aux Indes occidentales. “Two plantation workers - a man carrying a hoe and a woman holding an infant - walk uphill as goats forage and romp nearby. Grace Bay and mountains are seen in the background.” (Description from the first source)

The second and fourth details from the book are taken from the third aquatint Vue de l'Establissement des Missions a St. Johns dans l'Isle d'Antigon aux Indes occidentales. “The Moravian church, headquartered on St. John’s Street, was a set of simple stone buildings that served an overwhelming majority of enslaved black worshippers.”

Learning this led me down many different paths. The Moravian church mission was one of the Christian denominations in the Anglo Caribbean that supported emancipation, eager to see my ancestors fulfill their supposedly latent civilized potential once they became literate, abandoned their African spiritual beliefs and got married (for a start). Mary Prince, whose slave narrative is the most well-known from the Caribbean, was Moravian and lived for a time in Antigua. Her experiences there formed a notable part of her the narrative. And it may not surprise you to note that the first school Kincaid attended as a child was a Moravian school.

For the newsletter let us step through the aquatint portal to another Antiguan writer: Natasha Lightfoot, associate professor and all round bad ass historian, from whom I sourced the last aquatint description. (Spot the difference?) If you want a better understanding of A Small Place, especially Kincaid’s artful deconstruction of “emancipation”, you must read Lightfoot’s Troubling Freedom: Antigua and the Aftermath of British Emacipation (Duke University Press, 2015)—the cover also features a detail from the third aquatint. In examining the period right before and after emancipation she complicated more popular narratives of a unified community of African descendants resisting for the same goals. Instead she sifted through the different ideas of “freedom” among the newly emancipated; detailed how those different ideas clashed and, for some, were built on the oppression and marginilization of those presumably on the same side; and how both the colonial government’s and the Christian churches’ conception of freedom strangled the emancipation project.

P. S. If you’re familiar with art from this period, isn’t it curious how the art commissioned by both the pro-slavery plantation owners and the pro-emancipation missionaries portray the landscape and the people in exactly the same way?

The Writer

In Jamaica Kincaid: Writing Memory, Writing Back to the Mother (SUNY Press, 2006) J. Brooks Bouson examined two of Kincaid’s essays in the chapter “The Political is Personal in A Small Place and ‘On Seeing England for the First Time’”. She pieced together quotes from several different interviews, most of which were inaccessible to me, to provide insight into how the essay ended up as a book, Kincaid’s writing process, and the profound effect it had on her. A lot of persons tend to focus on the times Kincaid said, in different ways, that she wasn’t angry she merely told the truth. But I quite like Bouson’s focus on the interview moments when she claimed that anger. The excerpt shared here is on page 93 and can be read on Google Books.

Writing ‘A Small Place’, in Kincaid's account, helped her clarify her politics. "I didn't know that I thought those things. I didn't go around saying them to myself. But then, somehow, once I had the opportunity to think them, I just did. ... I wrote with a kind of recklessness in that book. I didn't know what I would say ahead of time. Once I wrote it I felt very radicalized by it." When reviewers repeatedly remarked on the book's anger, Kincaid came to "love anger" even more, insisting that "the first step to claiming yourself is anger. You get mad. And you can't do anything before you get angry. And I recommend getting very angry to everyone, anyone." In writing ‘A Small Place’, she realized that she "had all this feeling and that it was anger" and she wanted the book to be "crude and impolite-and all the other things that civilized people are not supposed to be" (Perry, "Interview" 498). Despite the openly political content of ‘A Small Place’, writing it for Kincaid was like "going to a psychiatrist”—it was "getting something" out of her head that if she had not would have driven her "absolutely insane" (Perry, "Interview" 498, Ferguson, "Interview" 174).

Paraphernalia

The Critics

All hail Edwidge Danticat’s second newsletter feature. In April 2022 she appeared on the Book Society podcast hosted by Lucas Cantor and gave a sharp, excellent critique of A Small Place, connecting it to her own work, to Haiti and the wider Caribbean. Not only did she concisely explain why tourism in the Caribbean is, in a unique way, a compromised product from conception, she corrected the framing of the Haitian Revolution as an offspring of the French Revolution, named another Kincaid text as a companion to A Small Place and much more. A rewarding listen especially for anyone who has not engaged much with Caribbean history as understood by someone of the region.

Edwidge Danticat and I Talk About A Small Place by Jamaica Kincaid

The Readings

“Race, Space & Architecture is a project a long time in the making. Manufactured in the magic, elastic now-now time of Southern Africa (from where its creators all hail), this is a site which has been pressed into being with care […] an open access curriculum shared as a work in progress. Here, we engage with three questions:

What are the spatial contours of capitalism that produce racial hierarchy and injustice?

What are the inventive repertoires of refusal, resistance and re-making that are neither reduced to nor exhausted by racial capitalism, and how are they spatialised?

How is ‘race’ configured differently across space, and how can a more expansive understanding of entangled world space broaden our imagination for teaching and learning?” - From the RSA website

The creators and contributors of this mind expanding project have contributed art, writings, sounds, and many other kinds of engagement. From the sounds section of the curriculum here is Adwoa Agyei reading an excerpt from A Small Place. (I love the crickets in the background.)

Adwoa Agyei reads from ‘A Small Place’ by Jamaica Kincaid

Peers without Realms

Natasha Lightfoot is an assistant professor of History at Columbia University from Antigua. She teaches Caribbean, Atlantic World, and African Diaspora History focusing on the subjects of slavery and emancipation, and black identities, politics, and cultures. The fantastic Caribbean history podcast Lest We Forget run by Tenement Yaad Media introduced me to Lightfoot and her scholarship. Listen to this episode about a post-Emancipation rebellion at which women of African descent were at the forefront. Of course, A Small Place is one of the books listed in the “Additional Knowledge” section.

And The Women Shall Lead Them: Antigua's 1858 Uprising

Art End Note

In the patreon-only bonus archive to the best interview podcast Between the Covers with David Naimon, Myriam J A Chancy read excerpts from A Small Place and connected them to her latest novel What Storm, What Thunder, set during the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. Like so many other Caribbean countries including Jamaica, Haitians too can recognise their country in Kincaid’s words.

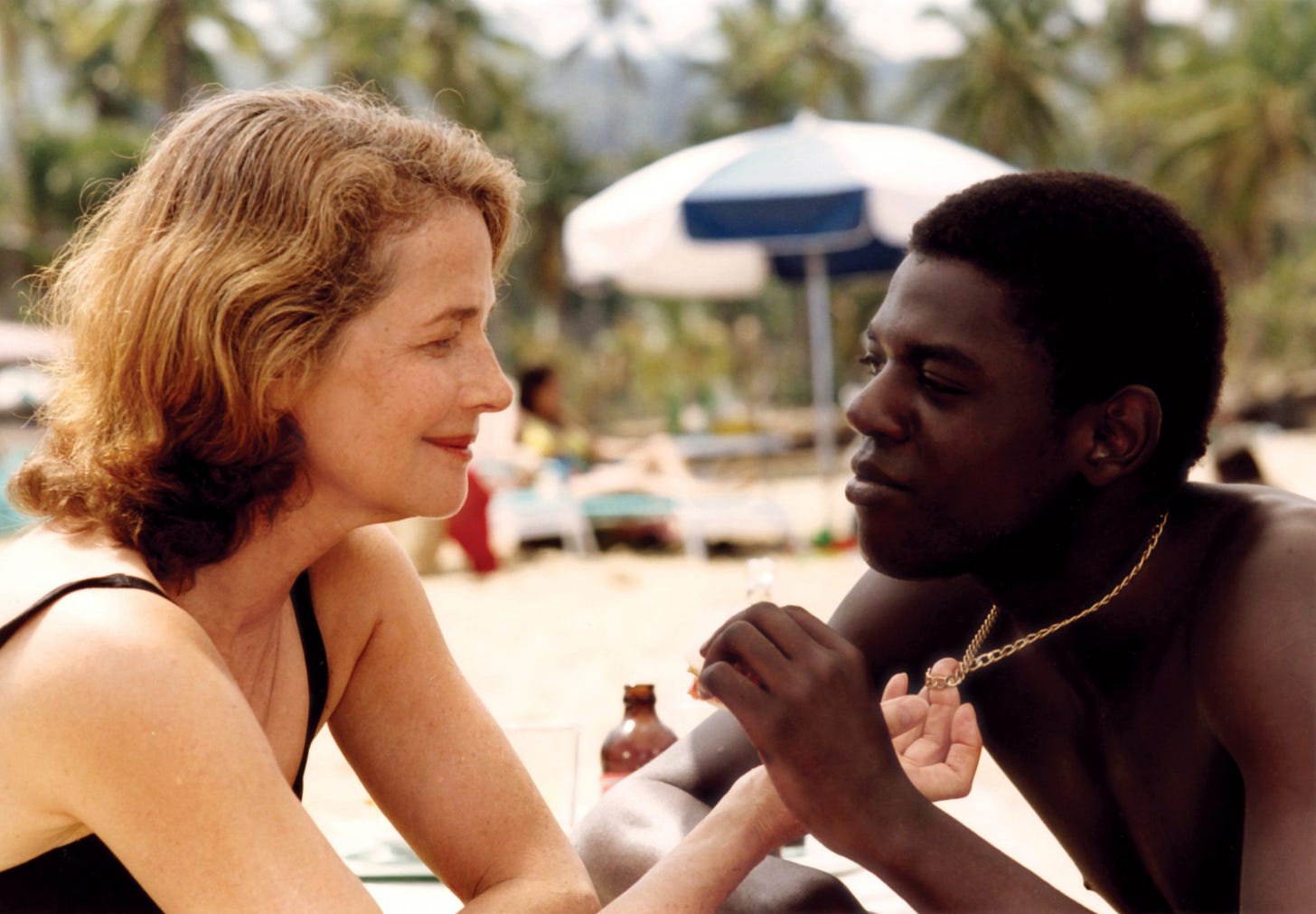

It is no surprise then that in 9 Books About Love, Loss, and Belonging Set in the Caribbean, a 2021 listicle she did for Electric Literature she included another book set in Haiti that addressed the dehumanising exploitation tourism produced: Haitian-Canadian author Dany Laferrière’s Heading South, translated by Wayne Grady. The film adaptation by French director Laurent Cantet with an adapted screeplay by him, Laferrière and Robin Campillo “[focuses] on relationships between foreign women who, while on vacation in Haiti, take Haitian male lovers without concern for their tenuous lives beyond the enclave of resort hotels.”

For the English speaking market, if you’re in Australia (or have a good VPN subscription) you can watch it on sites like Beema Film. For the rest of us it’s either DVD or a poor quality version on YouTube.

As an alternative there is the 2001 documentary Life & Debt directed by Stephanie Black in which she deployed striking quotes from A Small Place to give an all too relevant commentary on how the USA, Canada and Europe are addicted to fucking us over. Available on Amazon US.

Utilizing excerpts from the award-winning non-fiction text "A Small Place" by Jamaica Kincaid, Life & Debt is a woven tapestry of sequences focusing on the stories of individual Jamaicans whose strategies for survival and parameters of day-to-day existence are determined by the U.S. and other foreign economic agendas. By combining traditional documentary telling with a stylized narrative framework, the complexity of international lending, structural adjustment policies and free trade will be understood in the context of the day-to-day realities of the people whose lives they impact. - Film website

At the Close

This is a stacked newsletter but I enjoyed putting it all together. Please feel free to peruse it at leisure, giving your attention to different sections at different points throughout your reading of A Small Place. If you can I welcome donations, gift cards (from a Jamaican bookstore), or book wish list gifts in support of my efforts.

We will discuss A Small Place on Sunday, March 26th at 6:00 PM ET/Jamaican time. Sign up at Eventbrite!

If you’re interested in group discussions on the books otherwise join us on Discord. Here’s the new invite link: https://discord.gg/QVA7uWcc. (If you read this newsletter after the link expires feel free to contact me for a new one. My contact info is at the end if you’re reading by email.)

If you’re on Instagram be sure to tune in on Wednesday, March 8, at 7:30 PM ET/Jamaican time for an IG Live with me and Tanya Baston-Savage, publisher of Blue Banyan Books, as we discuss so-called difficult women in literature. Blue Banyan Books is a woman owned Caribbean publisher based in Jamaica that has published some of my favourite books.

All the best to you and yours as we read Kincaid in March!