The Book

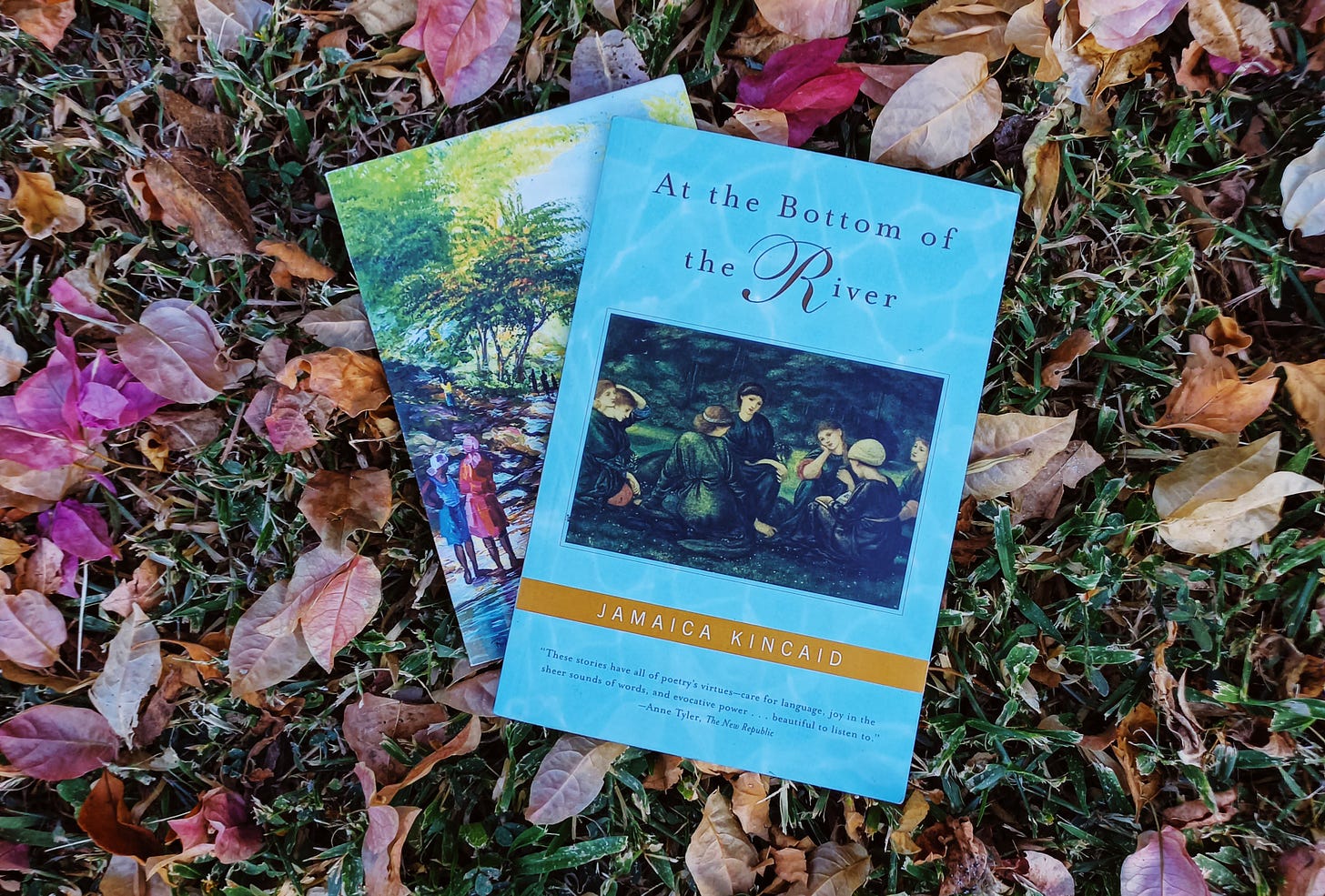

At the Bottom of the River by Jamaica Kincaid is a collection of short stories or prose poems depending on whose description you read. They were first originally published between the years 1973-1982 in “several magazines”, or “The New Yorker and The Paris Review”, or just “The New Yorker” if that publication’s glamour has a strong enough hold over your sources and therefore your brain (as it did mine, for a time). Originally published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 1983, it won the 1984 Morten Dauwen Zabel Award, a “$10,000 biennial award…established by a bequest from Morton Dauwen Zabel. It is given in rotation to a poet, writer of fiction, or critic, of progressive, original, and experimental tendencies.” Winners of the award before her include Joan Didion, Harold Bloom and more recently Frank Bidart, Yusef Komunyakaa and Claudia Rankine.

“Girl”, the collection’s opener, is Kincaid’s most anthologized piece of writing, included in writing guides the world over as she has pointed out. You would be forgiven if you thought there was nothing else in her debut of note. Of course, that was the story my mind blurred over to the next “In the Night” to sip it “like a sweet drink” (even if that wasn’t the kind of night the story was set in) as bird turned into a reasonable Ol’ Higue who admired honeybees, hisbiscus (one of my favourite flowers), and drank “the blood of her secret enemies”.

Impressions

After I wrote the first newsletter I started Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, translated by Richard Howard. The first page on which Barthes’ noted the different relationalities formed when as he beheld an 1852 photograph of Jerome, Napoleon’s younger brother, confirmed it as the right decision. “I am looking at eyes that looked at the Emperor.” I do think of At the Bottom of the River as both a book that Kincaid created and a contigency dependent on all of our readings to come into being, to transform, to always be in a state of about to be realized.

Part of the story “At Last” read like a series of photos put together. “Stand over there…we hid in this corner…I used to stand here, at this window…I used to stand here too.” In the first chapter Barthes wrote,

Show your photographs to someone—he will immediately show you his: “Look, this is my brother; this is me as a child,” etc.; the Photograph is never anything but an antiphon of “Look,” “See,” “Here it is”; it points a finger at certain vis-à-vis, and cannot escape this pure deictic language.

My reading felt very much directed by the speaker in Kincaid’s story guiding my gaze to there and over there too even if the writing did not have photography’s limitations as Barthes understood it. The shifts in the location often seemed instant, lending the speaker and whoever she spoke to a ghost-like quality and yes, Barthes saw “in every photograph: the return of the dead.”

But what of light? “(Where is the light?)” In “Wingless”! Lines of it repeated in multiple variations. Marina Tsvetaeva used Boris Pasternak’s poetry to define photography as “light writing” in Art in the Light of Conscience: Eight Essays on Poetry translated by Angela Livingstone. Kincaid’s writing here may not have, as Tsvetaeva saw in Pasternak’s, “banqueting of light”. It captured fields of shadow and the light there the better to show it.

But what do you think it’s about?

I read that this collection is about mothers and daughters, about the powerful and the powerless. I am only at the mid point. Maybe at the end these readings will excite me? I am not very good at judging what books are “about” and confess that I often find the question itself very boring, especially when it comes to critiques of Kincaid’s fiction. It may also be due to the fact that the writing thus far is queer as hell but I’ve yet to come across any critic who took that aspect seriously. I’ve shared story excerpts in the discord.

The Writer

Kincaid has given multiple writer origin stories. In the previous newsletter it was photography. In another interview I can no longer find she cited Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “In the Waiting Room” as one that influenced her, that ushered her into writing, or showed her that she could do it. (I know I did’t make it up because academics cite Ivan Kreilkamp’s 1996 Publisher’s Weekly interview but I don’t have access to it.) I couldn’t have been more eager to read the poem…and then I tripped over these lines.

My aunt was inside

what seemed like a long time

and while I waited I read

the National Geographic

(I could read) and carefully

studied the photographs:

the inside of a volcano,

black, and full of ashes;

then it was spilling over

in rivulets of fire.

Osa and Martin Johnson

dressed in riding breeches,

laced boots, and pith helmets.

A dead man slung on a pole

--"Long Pig," the caption said.

Babies with pointed heads

wound round and round with string;

black, naked women with necks

wound round and round with wire

like the necks of light bulbs.

Their breasts were horrifying.

The full poem can be read here.

There are obvious similarities between it and Kincaid’s early writing: the child speaker, the seemingly out of body examination of self. All the crafty things. And yet that horror sent me skedaddling out of the poem as if my life depended on it.

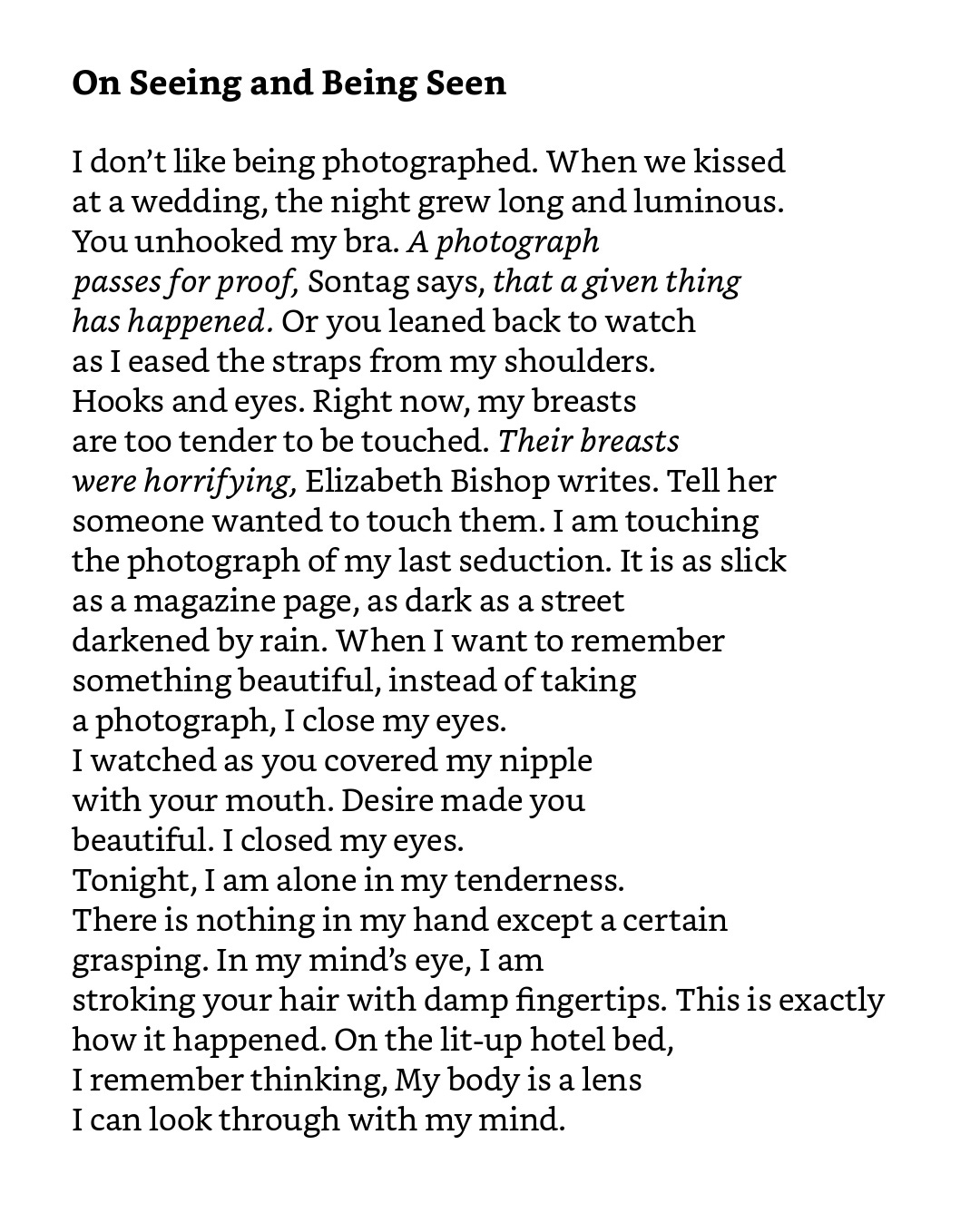

But the spirits are here and watching. Not too long after I listened to David Naimon’s Between the Cover podcast episode with Ama Codjoe. She read the poem “On Seeing and Being Seen” from her latest collection Bluest Nude:Poems (2022) out fromMilkweed Editions.

“Their breasts / were horrifying, Elizabeth Bishop writes. Tell her / someone wanted to touch them.” Yes. There are connections to Kincaid’s writing here too, especially in that last line. Perhaps as we continue to read Jamaica Kincaid her writing will offer us an opportunity to think more about different ways of seeing.

Paraphernalia

The interviews

Since I overtook that “The Writer” section with all my own ~feelings~ let me give you another origin story unadorned. It’s another excerpt from Moira Ferguson’s interview published in the Winter 1994 issue of The Kenyon Review under the title “A lot of Memory: An Interview with Jamaica Kincaid”.

MF: Growing up, did you recite narratives in your head? Rehearse conversations?

JK: Yes, I did that. I still do that, but I actually never connected that to actual writing. You know, I used to see my mother talk to herself a lot. And I'm telling you something new. It has just dawned on me that I would see her doing things, and she would have these long conversations with herself. Usually I would see her doing it when she was washing or scaling fish or cooking. And it is possible she is a writer too. That is just what I would have done. Yes, so I used to do that. And also the other thing is I used to daydream all the time and read all the time when I was a child and that was considered a really horrible thing. Everyone was very glad that I liked reading, and then it became this thing that I liked to do and didn't do anything else, so that became a problem.

The critics

I didn’t get much reading done during the holiday season. Two long essays from a 1989 and 1994 World Literature Today issues, both of which are freely available to read on JSTOR, were out to kill my whole vibes. In her 1989 essay “Merge and Separate: Jamaica Kincaid’s Fiction” Wendy Dutton viewed At the Bottom of the River and Annie John as two pieces of a whole: what the former obscured the latter clarified. Sure, okay, but this made me laugh:

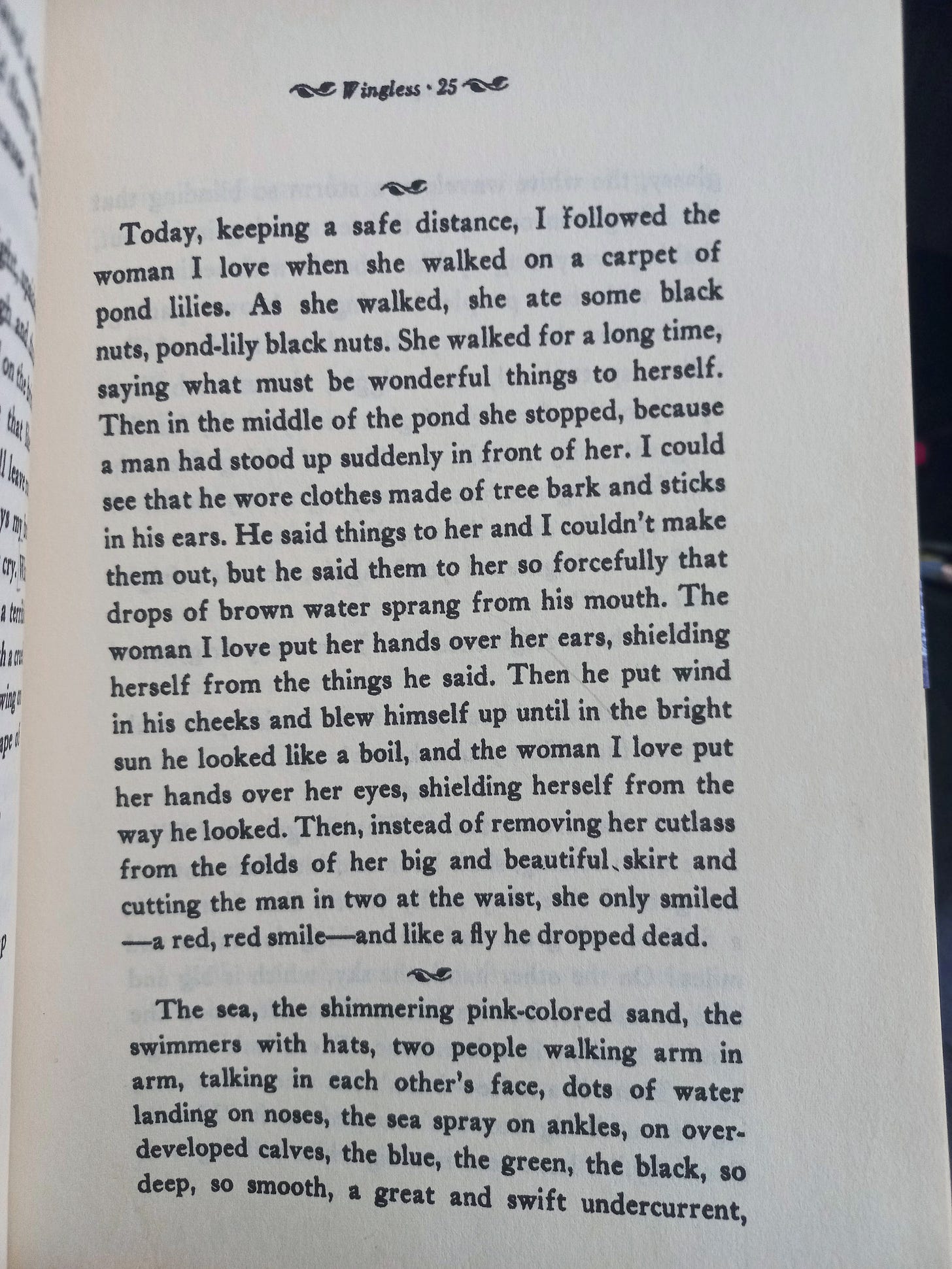

Another time Annie walks in on her parents as they are having sex. She coolly observes her mother's passion. The scene matches the powerful man-woman encounter that the girl witnesses in "Wingless," where the man's erection is described as follows: "Then he put wind in his cheeks and blew himself up until in the bright sun he looked like a boil."

That quote is on page twenty-five. Here is the full paragraph for your viewing pleasure.

Is…is that what happened? If you saw what she saw tell me everything.

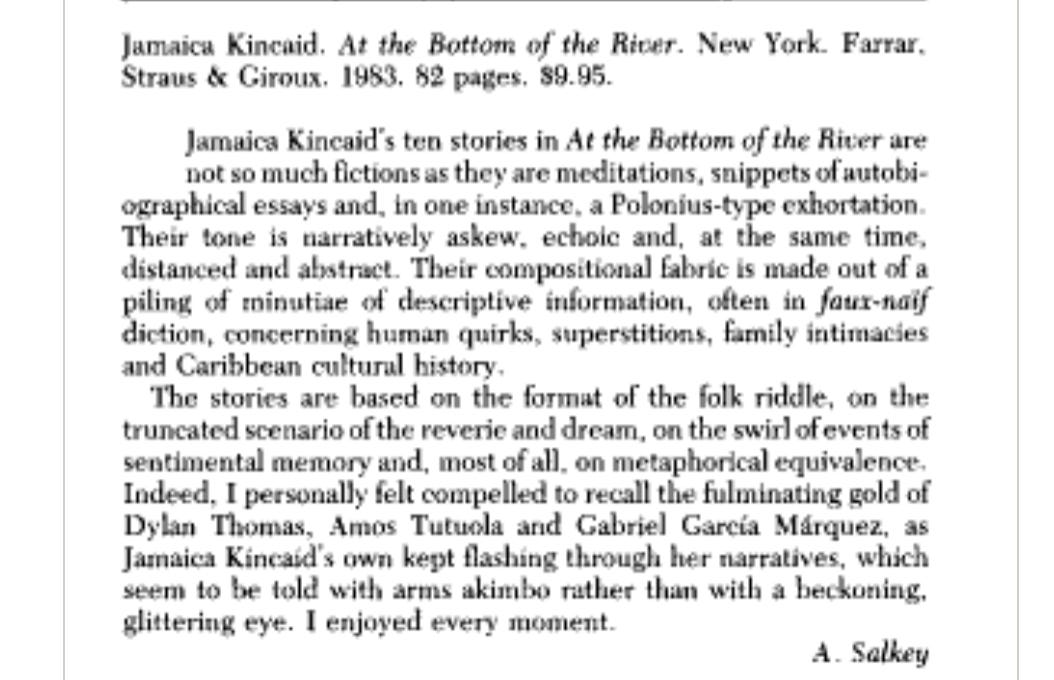

To make it up to myself here is a short notice from Andrew Salkey that appeared in the Spring 1984 issue of World Literature Today. Andrew Salkey (1928-1995) was a Jamaican novelist, poet, children's books writer and journalist of Jamaican and Panamanian origin…A prolific writer and editor, he was the author of more than 30 books in the course of his career, including novels for adults and for children, poetry collections, anthologies, travelogues and essays. (Wikipedia)

The Readings

The New Yorker has a podcast series in which authors select fiction from the magazine’s archive to read and briefly discuss. My newsletter didn’t touch on At the Bottom of the River’s sonic quality but Edwidge Danticat came to the rescue with her podcast episode. Before she read “The Girl” (1978) and “Wingless” (1979) Danticat spoke about her first encounter with the author in university, the similarities between Kincaid’s debut and the latest novel See Now Then, why the stories call to be read out loud, and much more. She herself is regular contributor to the magazine.

Edwidge Danticat (b. 1969) is the author of several books, including Breath, Eyes, Memory, an Oprah Book Club selection, Krik? Krak!, a National Book Award finalist, The Farming of Bones, The Dew Breaker, Brother, I’m Dying…and Everything Inside, a Reese’s Book Club selection, and National Book Critics Circle Awards winner. (Author website)

Edwidge Danticat reads Jamaica Kincaid

Peers without Realms

Ama Codjoe (b.1979) is the author of Bluest Nude (Milkweed Editions, 2022) and Blood of the Air (Northwestern University Press, 2020), winner of the Drinking Gourd Chapbook Poetry Prize. She has been awarded support from Bogliasco, Cave Canem, Robert Rauschenberg, and Saltonstall foundations as well as from Callaloo Creative Writing Workshop, Hedgebrook, Yaddo, Hawthornden, and MacDowell. She is a sister in the collective Poets at the End of the World. Five poets: Ama Codjoe, Donika Kelly, Nicole Sealey, Evie Shockley, and Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon…are influenced by the work and lives of Gwendolyn Brooks, Lucille Clifton, June Jordan, and Audre Lorde to turn literary work into action. (Source: author website and Between the Covers podcast)

I cannot recommend her interview with David Naimon enough. It will double as my Art End Note because they both explore art, particular artists and the world views that inform them in ways that absolutely connect to Kincaid’s writing. And there’s a transcript!

Between the Covers podcast with Ama Codjoe

I bought her newest book and became a Between the Covers listener supporter with the help of your donations to this project. (A Caribbean writer examined A Small Place as their contribution to the bonus archive!) My thinking and writing have and will continue to be informed by Naimon’s work. If you’re interested in supporting We Read Jamaica Kincaid you can donate to my Paypal. Many thanks to all those who have contributed. I truly would not have been able to do this much without you.

At the Close

2023 is finally here. We’ve started our first book and the discord is filling up. Here’s the new invite link: https://discord.gg/KbSFJZfm. (If you read this newsletter after the link expires feel free to contact me for a new one. My contact info is at the end.) All book channels are open but scheduled we’ve-all-read-it-what-fun-let’s-gab discussion will be on the last Sunday in January with the Zoom link-up on the Monday. All relevant info will be in the discord.

Happy New Year!