What’s Inside

For Your Consideration: A call for contributions from those reading Kincaid in translation

The Book: Publication history

Impressions: Musings on queerdom, unruly girls, and my intense, unsettled history with this text

The writer: Jamaica Kincaid’s history with Caribbean literature

Paraphernalia: Film and video interview recommendations

At the Close: Zoom discussions and Discord details, new logo fanciness

For Your Consideration

A call for contributors

Are you reading Jamaica Kincaid in translation? I would love to share your experience with other newsletter readers, nothing more than a paragraph or two. Send submissions to my email ifthisisparadise@gmail.com with the subject “Kincaid in Translation”. If featured you would receive a token payment of $10 USD funded solely by me with the help of reader donations. If this is a feature you’d love to see in the newsletter or you simply want to support the We Read Jamaica Kincaid project you can donate here.

On to our girl, Annie.

The Book

Annie John was first published as a series of stories in the New Yorker, presumably from 1983-1984, “in slightly different form”. If you are a subscriber you may access the online archive and read them yourself to compare. (Please be as obsessed as me, read them and report back. Tell me everything.)

Hill & Wang, an imprint of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, published the novel in 1985. Hill and Wang was originally an independent publishing house founded by Laurence Hill and Arthur Wang in 1956 (according to this paywalled Oxford Companion to the Book). By the time FSG bought it in 1971, Henry Raymont in The New York Times (gifted link) described it as a publisher that “for more than a decade specialized…in American history and drama books”. (Raymont dated its founding to 1959 but the NYT 2005 obituary (gifted) for Arthur Wang by Dinitia Smith aligned with Oxford.) Hill left the company with the 1971 sale but Wang stayed on and “remained active in the company until 1998.”

As an independent house Hill & Wang published Langston Hughes, Elie Wiesel’s memoir Night, and Richard Howard’s translations of Roland Barthes! which is a pleasing coincidence.

Annie John was nominated for the L. A. Times Book Prize for fiction but lost to Louise Erdrich’s Love Medicine. In 2010 the Centre for Fiction awarded Annie John its Clifton Fadiman Medal given to backlist titles at least a decade old written by a living author.

Its UK publishing path is more opaque to me. There’s a Vintage UK (Penguin Random House) edition floating around but in the newer one from Picador UK (Macmillan) its copyright page claims it published the original back in 1985. But the new UK editions are the result of them winning the rights in auction back in 2020. I guess they lost them along the way…?

Impressions

Jamaica Kincaid’s first novel holds a special status among a generation of queer Caribbean women in the region. It was (and may still be) a popularly assigned text in Anglo-Caribbean high schools. Kincaid herself has gradually come around to publicly acknowledge what she described as “latent lesbianism” in her Paris Review interview published last year. Her earlier denials stood in strange contrast to its general reputation among students that I knew, certainly at the boarding school I attended—its reputation as “the lesbian book”. Georgia P. Love, a long time advocate in the queer/gender/art spaces in Jamaica, wrote

Annie John by Jamaica Kincaid may have been the dark rabbit hole that led me tumbling unconsciously into a world of black feminisms. At 13 years old when many of my classmates had decided it was “nasty” and “weird” because of its explorations of sexuality and intimacy between women, I remember devouring it and feeling an intuitional ease with Annie.

In other ways, Kincaid’s denial was not particuarly strange when we consider that '…terms like "heterosexual", "homosexuality", and "lesbian" are beside the point since they connote politicized mainland labels, which according to Natasha Tinsley are inadequate for characterizing Caribbean sexualities.’ - Akash Nikolas, 'Straight Growth and the Imperial Alternative: Queer Reading Jamaica Kincaid' (2017)

I’ve been dipping in and out of Kaiama L. Glover’s A Regarded Self: Caribbean Womanhood and the Ethics of Disorderly Being, a book in which she “champions unruly female protagonists who adamantly refuse the constraints of coercive communities.” One of the characters she foregrounds is Xuela, the protagonist of Kincaid’s The Autobiography of My Mother. Here are some quotes from the introduction.

All of these women engage in some degrees of narcissistic pushback with respect to persistent, structural social trauma—self-regard is the tactic they adopt in the face of impossible satisfaction from their community.

Further, as Donette Francis reminds us, “conditions of belonging presuppose a raced, gendered, classed, and sexed body, and…for women and girls the struggles have often been against kin as much as colonizer”.

Insofar as distinction is maintained between the notion of communal identity and that of bourgeois individualism, I am interested in the space between the presumed virtue of the one and the unseemliness of the other.

I want to look closely, that is, at texts in which the female protagonists do not behave in ways that fit asserted parameters of feminine solidarity—characters who…are not generatively linked to mothers and daugthers…

Recognising that Annie John was the progenitor of Kincaid’s women I perhaps better understand why Annie is, for many, an unlikeable character. (This group includes Claire Fuller who rated it three stars on Goodreads because Annie hated everyone and was so horrible at the end. I am largely unfamiliar with Fuller’s prose and am content, nay pleased, to remain so.)

This will be my fourth time reading it. I have quite an…intense history with this book as a queer reader who didn’t always want to know herself. I remember almost nothing about the first, too much/not enough about second and third (done in quick succession last year). I wish I could explain my unease about this re-read after everything.

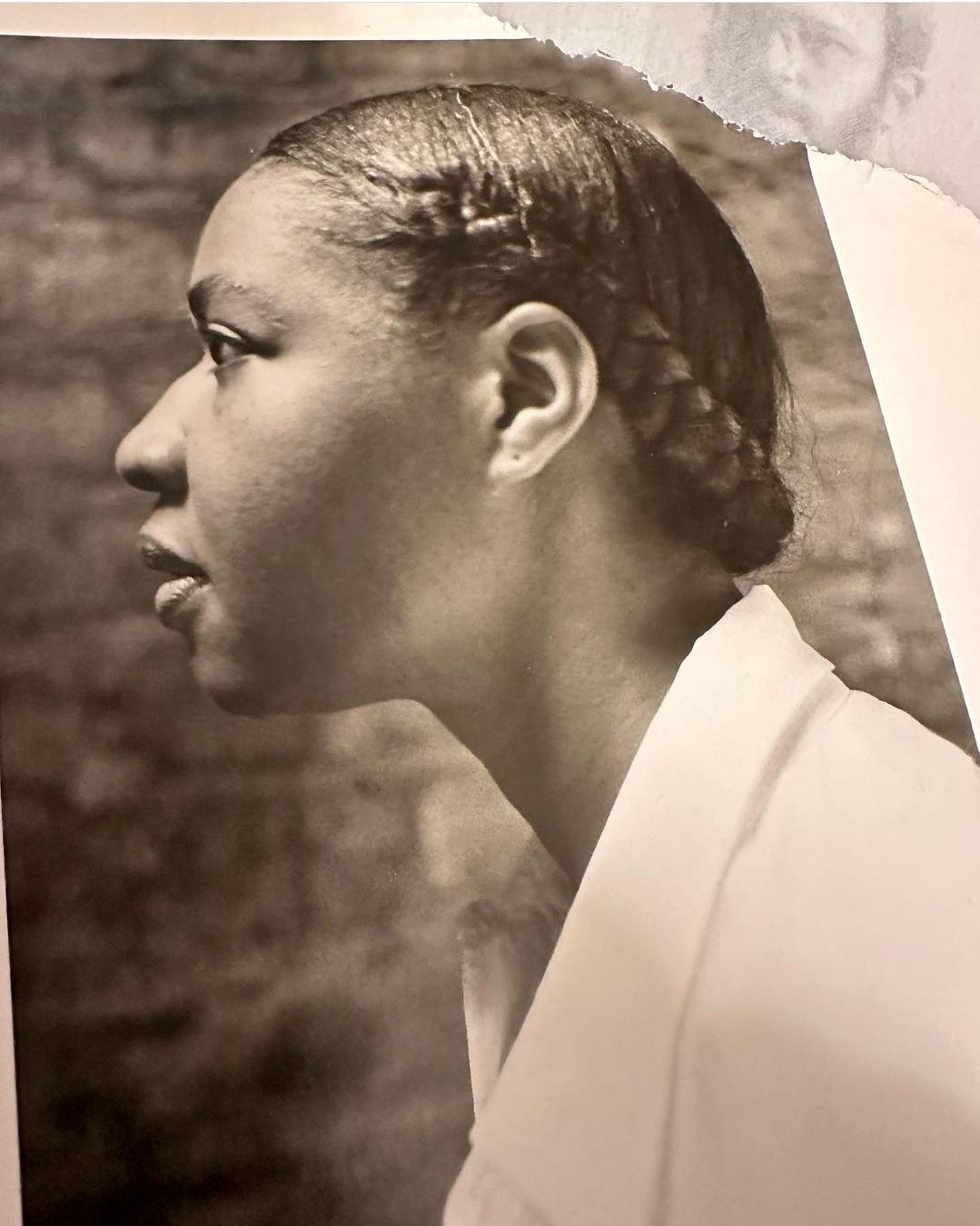

Wendy Dutton compared Annie John to a photo album that only “looks at the surface of things and lacks rationale, explanation, motivation” compared to the “cerebral text” that is At the Bottom of the River in her 1989 essay “Merge and Separate: Jamaica Kincaid’s Fiction” in World Literature Today. I wish I felt that way. Now, to contemplate that turning to the first page feels like too much. “I feel myself observed by the lens”, Kincaid as the photographer/operator. I cannot “transform myself in advance”, I don’t want to, I am pinned. When the photos fall and I become the observed object on page after page after page the punctum (“the element which rises from the scene, shoots out from it like an arrow, and pierces”) will overwhelm me. I will want to scrub it out.

The Writer

It may surprise some to learn that up to this point in her writing career Kincaid had never read another Caribbean writer. She grew up in colonial Antigua, educated according to a British curriculum. She went to the USA rather then the UK which was where Anglo-Caribbean writers tended to end up; nor did she seek out a Caribbean community in New York. She had read African-American writers. I am fascinated with this disorderly writer who did not do many of the things I’ve heard Caribbean writers did or ought to do to yet created prose more piercing, inventive, uncontainable, and lasting than those more strongly associated with the so-called progressive idealogies at the time. Here is Kincaid quoted from Moira Ferguson’s interview “A Lot of Memory”, published in The Kenyon Review’s Winter 1994 issue.

My writing, if I owe anybody, it would be Charlotte Bronte. It would be English people. It would be Virginia Woolf. It would be Wordsworth, it would be Shakespeare, it woul be the King James version of the Bible. I had never read a West Indian writer when I started to write. Never. I didn't even know there was such a thing, until I met Derek Walcott. He said "Do you know-?" I had never heard of them, so I can't remember who he said. And I said no. And he made a list of people for me to read. There was not one woman on it, by the way. And that is how I knew there was such a thing as a West Indian writer.

Paraphernalia

Art End Notes

Rain (2008) is a Bahamian film written and directed by Maria Govan, starring Renei Brown as the titular character alongside familiar figures like CCH Pounder. Although the mother daughter is quite different from the characters in Annie John many elements like the daughter’s association with rain, conformist colonial school systems and societal configurations of womanhood, the retention of folk knowledge, and the prominent centering of relationships amongst women and girls are more than enough to make the connection. Some reviewers deemed it cliché but I loved everything about this story oriented around a dark skinned Caribbean girl in fractious relationship with her mother.

Available to stream in the iTunes store (according to the internet). I watched it on Caribbean Tales TV. (Offers a one week free trial.)

Peers without Realms

Kaiama L. Glover is the Ann Whitney Olin Professor of French and Africana Studies at Barnard College, Columbia University. She is coeditor of The Haiti Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Duke University Press), the author of A Regarded Self: Caribbean Womanhood and the Ethics of Disorderly Being (Duke Uni Press), Haiti Unbound: A Spiralist Challenge to the Postcolonial Canon (Liverpool University Press), and a translator of Haitian fiction such as Hadriana in All My Dreams by René Depestre (US: Akashic, UK: Jacaranda) and Sweet Undoings by Yanick Lahens (Deep Vellum) out April 11.

She and Tami Navarro, an Assistant Professor of Pan-African Studies at Drew University, have over the years created a remarkable archive of conversations with Caribbean writers. There is the Writing Home podcast series and the Caribbean Feminisms video series. In Caribbean Feminisms Glover moderated a discussion between two Caribbean women writers of different generations. In April 2015 the duo was Jamaica Kincaid and Tiphanie Yanique, an award winning Virgin Islands author of several books including the novels Monster in the Middle (Riverhead), Land of Love and Drowning (Riverhead), and the short stories collection How to Escape from a Leper Colony (Graywolf Press). They discussed “their experiences as women of color from the Caribbean, their thoughts on writing about the Caribbean region, and their engagement with gender and feminism in their writings.”

Caribbean Feminisms on the Page

At the Close

We had our first Zoom Link Up to discuss At the Bottom of the River this past Sunday. It was wonderful! Thanks so much to everyone who attended. I received requests for recordings but per my own inclinations and some participants I will not record meetings for later viewing. I know this will prove inconvenient for some but my instinct is always to reserve the intimacy of a space over leaving a record (as that is typically understood these days).

We will discuss Annie John on Sunday, February 26th at 6:00 PM ET/Jamaican time. Sign up at Eventbrite!

If you’re interested in group discussions on the books otherwise join us on Discord. Here’s the new invite link: https://discord.gg/r5E46CPn. (If you read this newsletter after the link expires feel free to contact me for a new one. My contact info is at the end if you’re reading by email.) All book channels are open but scheduled we’ve-all-read-it-what-fun-let’s-gab discussion will be on the last Sunday of this month.

I’ve upgraded my logo look for the newsletter and discord thanks to Kerine Wint’s amazing desgin skills! She’s a reviewer, columnist, and editor in SFF as well as a podcaster and designer. Thanks so much, Kerine.

Happy Kincaid February!