What’s Inside

The Book: Publication history with a likkle mix up

Impressions: Wayward Lucy and her kin

The Writer: “How was I not afraid?” The risk in self-invention

Paraphernalia: Another Lucy + Shakespeare, a Harlem Renaissance reading, a corrective to woeful podcast commentary and more

At the Close: Change in reading schedule and meeting time, the We Talk Jamaica Kincaid conversation series, new discord invitation, details on how to further support my work

The Book

Lucy was Jamaica Kincaid’s fourth book and second novel published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 1990. It marked the return of her fiction first appearing in The New Yorker. It did not restore any amiability to her working relationship with editor Robert Gottlieb who had rejected A Small Place out of hand. Leslie Garis “who often writes on the arts” noted in her October 1990 New York Times profile of Kincaid (gifted link) that a change Gottlieb wanted to make to what became Lucy was enough to keep him on her shit list. (Otherwise known as “not on speaking terms”.)

It was Kincaid’s first book set entirely in the United States. That fact paired with her autobiographical tendencies meant she was in closer proximity to whoever inspired her work. Michael Arlen, a man she once worked for, became her colleague at The New Yorker many years later.

Arlen is divorced from his first wife and has remarried, and perhaps it is that parallel between his life and the fictional lawyer in the book that has most upset some of Kincaid's friends and colleagues, including the writer George W. S. Trow, to whom the book is dedicated. When I asked him what he thought about her writing this book, he said, ''I didn't like it, but that's her privilege.''

George W. S. Trow, if you remember, was the friend who introduced her to William Shawn when he was editor at The New Yorker. Arlen himself felt differently.

Arlen, however, who has written both fiction and memoir, is keenly aware of the difference between the two forms and disagrees with the notion that a novelist might simply transcribe reality onto the page. ''It's an attitude that seems disrespectful of a fiction writer's ability to create fictional characters,'' he says.

Impressions

A We Read Jamaica Kincaid supporter bought from my wishlist Saidiya Hartman’s 2019 text Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals. I could not get Kincaid out of my mind as I read it. In reading her “critical fabulations” of the lives of the “rambunctious girls...anarchists, lady lovers, bull daggers, and wild women” moving north from the southern USA post-Reconstruction she named domestic labour as an afterlife of slavery. Servitude.

Kincaid continued the migration journey started in Annie John (1985) except that the destination was an unnamed US city most assume was New York, not England, Lucy was the character, and she was an au pair to an upper class white nuclear family, not a hospital nurse. On the train ride for an annual trip to the family’s summer home, Mariah, her employer, pointed to fields they passed.

Early that morning, Mariah left her own compartment to come and tell me that we were passing through some of those freshly plowed fields she loved so much. She drew up my blind, and when I saw mile after mile of turned-up earth, I said, a cruel tone to my voice, “Well, thank God I didn't have to do that.” I don't know if she understood what I meant, for in that one statement I meant many different things.

The fields hold memories and so do their dwellings especially for those who do “live-in” work. Lucy did, like Kincaid did, some of my family did, and now there is a family friend who wants her daughter, who is a paralegal here, to get her foot in the US immigration door through nanny work. We are caught in systems designed to extend and expand the plantation’s spatial and temporal enclosures. Particular national leaders carry out the charade of being against “illegal migration”. The truth is their economies depend on a steady stream of migration from places like Antigua and Jamaica, whether documented or otherwise. It’s all business.

***

A small rented room was a laboratory for trying to live free in a world where freedom was thwarted, elusive, deferred, anticipated rather than actualized.

Hartman. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments

I knew very little about Lucy before I started it last month. I was not prepared for her constant questioning and seeking, her reliance on her own mind and experience to fashion a life for herself rather unlike anything she knew before. Lucy’s domestic work did not carry all the horror it could have but she was still resistant, refusing to settle into any one thing for too long, even if it seemed the safest thing the world had to offer her.

I thought, On the one hand there was a girl being beaten by a man she could not see; on the other there was a girl getting her throat cut by a man she could see. In this great big world, why should my life be reduced to these two possibilities?

***

The revolt of black women against “the personal degradation of their work” and “unjust labor conditions,” expressed itself in militant refusals…Yet it had no chronicler. None responded to the call to write the great servant-girl novel.

Hartman. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments

You could name some now, I hope. My submission is The Confessions of Frannie Langton by Sara Collins, a 2019 novel about a 19th century Jamaican woman, maid, writer, light of my life, raised on a Jamaican plantation and taken to England as a young woman. From one of my book posts:

When she arrives in London she is electric with what she sees as an opportunity to make something more of herself and her life, more than what others make of her, beyond what they deny her. She is ready to self-actualize. Just like all the other 19th century heroes and heroines I'd read about. But here the stakes have never been higher! because of who and what she was at the centre of empire in 1825 England.

In Frannie’s own words:

Freedom can't be bought with anything a woman like me has to spend, but there are numberless choices between lying down or putting up a fight.

There are histories and spirits moving through these women, real and imagined, still.

The Writer

In considering Hartman’s along with Kaiama L. Glover’s Regarded Self writings on “unruly female protagonists who adamantly refuse the constraints of coercive communities” (mentioned in the Annie John newsletter), Kay Bonnetti’s Kincaid interview from a 1992 Missouri Review issue offers a lot for further rumination. I’ve pieced together two excerpts below. The full interview is freely available here.

Bonetti: Ms. Kincaid, in the novel Lucy, you give Lucy Josephine Potter one of your birth names and your own birthday. How closely do the facts of Lucy’s biography match your own?

Kincaid: She had to have a birth-date so why not mine? She was going to have a name that would refer to the slave part of her history, so why not my own? I write about myself for the most part, and about things that have happened to me. Everything I say is true, and everything I say is not true. You couldn’t admit any of it to a court of law. It would not be good evidence.

[…]

Bonetti: Perhaps I am identifying you too strongly with your characters, but Lucy talks about the fact that she realizes she’s inventing herself when she starts studying photography, and you too studied photography at a certain point after you got here.

Kincaid: I didn’t have the words for it, but yes, I was inventing myself. I didn’t make up a past that I didn’t have. I just made my present different from my past. How did I really do that? Just a few years off the banana boat basically, and there I was doing one crazy thing after another. How was I not afraid? The crucial thing was that I would not communicate with my family. Somehow I knew that was the key to anything I wanted to make of myself. I could not be with people who knew me so well that they knew just what I was capable of. I had to be with people who thought whatever I said went.

Paraphernalia

Art End Notes

The questionable cover art on the FSG edition of Lucy perhaps begged for more cover art commentary like in the previous newsletter. However, my clicks through different articles led me to Caroline Randall Williams’ Lucy, Negro Redux: The Bard, a Book, and a Ballet (Third Man Books, 2019). Who was this other Lucy? From Williams herself:

I got it into my head that Shakespeare had a black lover, and that this woman was the subject of sonnets 127 to 154. These sonnets have been called the “Dark Lady” sonnets for quite a while now, because of their focus…on a woman who consistently figures as “dark,” or “black,” in his description of her.

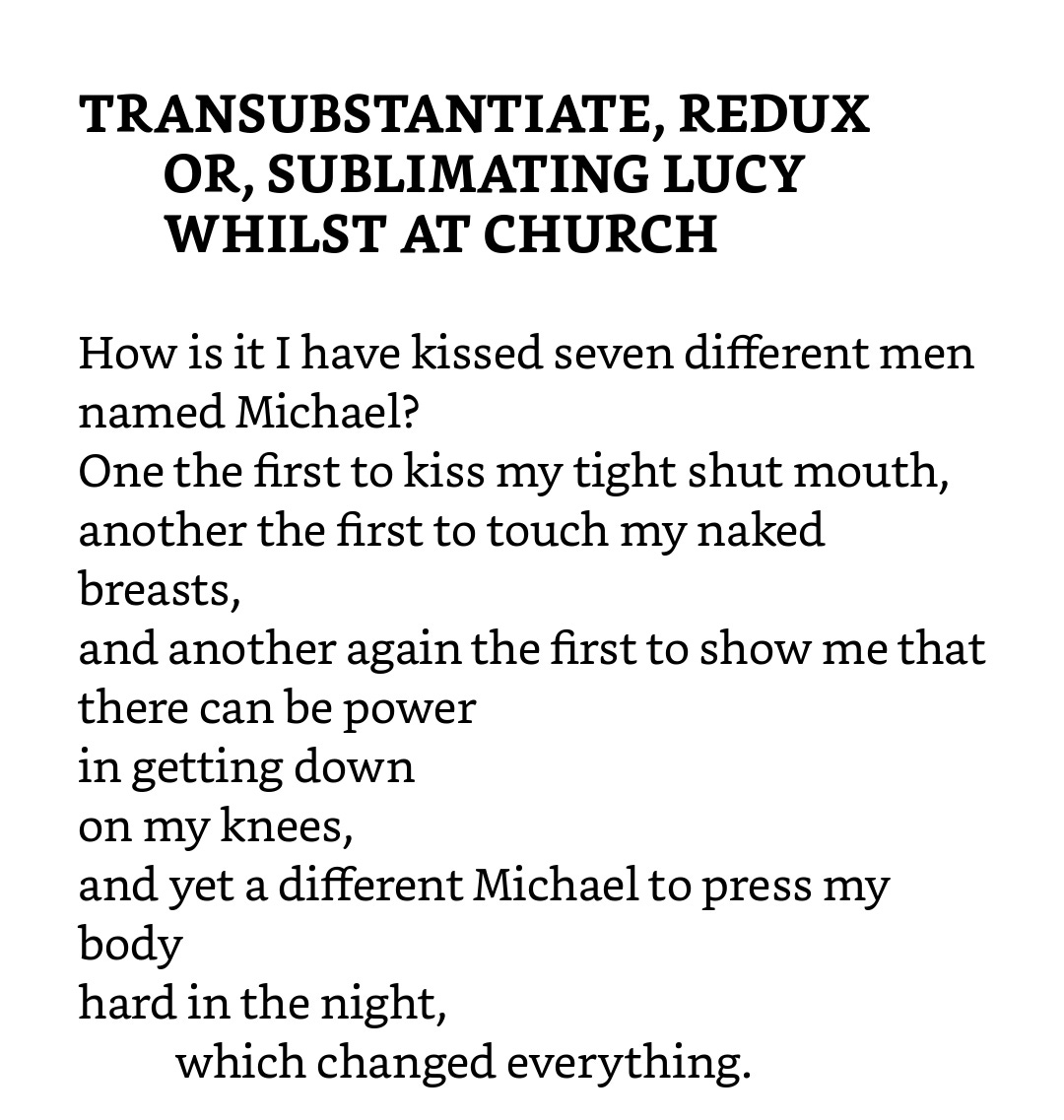

Reading some of the poetry I detected similarities between how they wrote Lucy with a frank sexuality that I doubt I will ever cease to find refreshing. Below is a screenshot excerpt from the poem “Transubstantiate, Redux Or, Sublimating Lucy Whilst at Church”.

Described as “a hybrid document [that] harnesses blues poetry, deconstructed sonnets, historical documents and lyric essays to tell the challenging, many-faceted story of the Dark Lady, her Shakespeare, and their real and imagined milieu” I had to add a copy to my cart. And yes, there is also a ballet adaptation choreographed by Paul Vasterling with music composed by Rhiannon Giddens (!!!) and Francesco Turrisi. Here is the New York Times article (gifted) about the ballet adaptation and a 5 minute video clip from the Nashville Ballet performance.

Lucy, Negro Redux (Nashville Ballet)

The Critics

In prepping for this newsletter I came across a podcast named “The Lit Century” which featured an episode about Lucy. In the episode synopsis Lucy is described as “triumphantly selfish”. The egregious misreading should have been a red flag but I am the saint who listened to it for maybe 7 minutes before abandoning ship. ( V. V. Ganeshananthan contributions were the only good thing—I could hear her think about how to respond to the white nonsense. She has a new novel out! Support writers who can read please do you see who else is getting published for the love of gad.)

For sophisticated analysis below is an excerpt from Sarah-anne Gresham’s concise 5 star bookstagram review. Sarah-anne is a Ph.D. student in Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Rutgers University, a co-founder of Intersect Antigua, a board director of Equality Fund, and a Fulbright Scholar from Kincaid’s birthplace.

Lucy “affects to be intoxicated with sights and suggestions,” to lose her sadness in her new home, but is perpetually disappointed. Compounding her disillusionment is her strained relationship with her mother, the memory of which succeeds in tempering the homesickness she feels for her island home. Abandoning colonial value judgments about sexuality, Lucy also unapologetically pursues sexual relationships with several men in her quest to invent herself in her own image.

Peers without Realms

Saidiya Hartman was born and raised in New York City. She is a Professor in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University. She is the author of Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth Century America (Oxford, 1997), Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2007), and Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (W. W. Norton, 2019) . She has published articles on slavery, the archive, and the city, including “The Terrible Beauty of the Slum,” “Venus in Two Acts” and “The Belly of the World.” She has been a Cullman Fellow at the New York Public Library, a Fulbright Scholar in Ghana, a Whitney Oates Fellow at Princeton University, and a Rockefeller Fellow at Brown University.

It was such a treat to learn that Hartman had done her own interview with Jamaica Kincaid in 2010. Here is a video of the event done as part of Kincaid’s promotion for her most recent novel See Now Then.

Readings

Lucy’s adjustments to her first winter, her yearning for home cooked food are such familiar hallmarks in migrant literature. Harlem Shadows (1922) by Claude McKay is a poetry collection that marks that transition as well. Even his migratory work patterns from city to New England summers and back again matched Lucy’s. Idle searching led me to the 1954 Anthology of Negro Poetry album edited by Arna Bontemps which included Claude McKay reading some of his own work.

I cherish the opportunity to share his work in his own voice, in this instance, his poem “Tropics in New York”. For so long, mostly exposed to dominant US media sources, I understood Claude McKay as an “American” literary figure in which Jamaica was only a footnote. But when you listen to this reading you understand that anyone who heard him in his time could not miss the fact that he was, among so many things, Jamaican. (Country yute, yuh know.)

At the Close

We have officially entered the bi-monthly portion of the reading schedule which will continue till the end of our reading project in August 2024. (Full reading schedule here.) That means our Zoom Link Up for Lucy will be in May on Monday 29th at 6:00 PM, Jamaican Time. Please note the temporary switch to Monday from the usual Sunday and to the time changes some of you may have experienced. Sign up at Eventbrite.

If you’re interested in group discussions on the books otherwise join us on Discord. Here’s the new invite link: https://discord.gg/t5ud9aky. (If you read this newsletter after the link expires feel free to contact me for a new one. My contact info is at the end if you read by email.)

The Zoom date change is to acccommodate my attendance at the Calabash Literary Festival in May. If you plan to attend please say hi when you see me! I would love to gab with you.

If you are glum about having to wait two whole months to talk about Kincaid, fret not. April will see the launch of a new addition to the We Read Jamaica Kincaid project: We Talk Jamaica Kincaid! It’s a conversation series that will happen (mostly) on Instagram Live between myself and another literary gem about all things Kincaid and anything related to her and her work.

My first guest will be Naomi Jackson, author of the novel The Starside of Bird Hill (Penguin, 2015). She is Assistant Professor of English and Creative Writing at Rutgers University-Newark. She was a 2021-2022 Scholar-in-Residence at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and served as Writer-in-Residence at Queens College. Our Instagram Live is scheduled to be on Saturday, April 29th. Once I get all the details locked down you will receive a short email with all the info and event sign up information you need.

As usual I appreciate any additional support you can give to my work in the form of money, book store gift cards or purchases from my Amazon or Bookshop wishlists (which have a US shipping address). Heartfelt gratitude to all those who have done so thus far.

Merry Kincaid reading!

I just finished Lucy (late as always) and immediately came to read your newsletter. Thank you for all of this. There is an endlessness I felt while reading this book—whole histories and lives and echoes and futures packed into every sentence. The expansiveness of your thinking and everything you speak of and reference here is proof of that, and invitation. I have just barley begun to think about it all.

What joy to read you reading LUCY alongside WAYWARD LIVES. When I think about Lucy, which I do at least weekly, as though she were a very real person I had very really met, I think about the way she (among so many things) makes the invisible refusals of white imperialism visible. I see so clearly, reading LUCY, how many things a white imperialist history refused her, refused her mother, before either were even born, how many things Mariah and Mariah’s milieu refuse Lucy in particular. Lucy’s refusals are only so glaring because they are not permissible… which I guess is why those podcasters see her as selfish, yes? She refuses to only be refused without refusing in turn?

I can’t wait for the Zoom conversation. Thank you for all this good work.